International Affairs – Garage Band

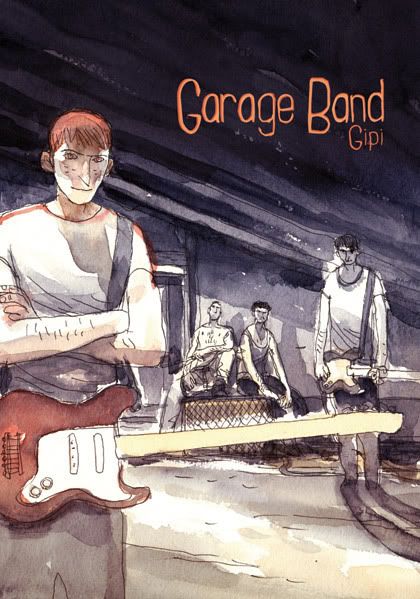

As mentioned recently, we at the LOD are going to be focusing more in the coming weeks on some foreign comics work, and I wanted to kick things off in style, with one of the most impressive books I’ve read so far this year. And that is Garage Band, the strange rumination on adolescence and music and garages by Italian creator Gipi. Originally published in France in 2005, the book now makes it’s U.S. debut courtesy of First Second books (and when it comes to finding great foreign comics work, they’re pretty much as good as it gets, but more on that later).

Garage Band follows four friends as they embark on the ambitious task of creating a great band. Their first big break comes at the book’s beginning as the father of the main character, Giuliano, allows the group to use his garage to practice. In their still-young minds, this all but guarantees their dreams of fame will come true. As Giuliano explains to his girlfriend, “We’ll get some songs ready, and then we’ll see. Everything’s different now we’ve got the garage.” The book varies harshly from any kind of expected foray into the well traveled lands of wide-eyed if naive youngsters challenging all the odds in the pursuit of success. Instead of a strong plot line carrying the teens through the story, the plot serves more as just an introduction into their surprisingly complex and troubled lives.

Garage Band follows four friends as they embark on the ambitious task of creating a great band. Their first big break comes at the book’s beginning as the father of the main character, Giuliano, allows the group to use his garage to practice. In their still-young minds, this all but guarantees their dreams of fame will come true. As Giuliano explains to his girlfriend, “We’ll get some songs ready, and then we’ll see. Everything’s different now we’ve got the garage.” The book varies harshly from any kind of expected foray into the well traveled lands of wide-eyed if naive youngsters challenging all the odds in the pursuit of success. Instead of a strong plot line carrying the teens through the story, the plot serves more as just an introduction into their surprisingly complex and troubled lives.

Aside from Giuliano, each of the characters is borderline unlikeable in places, mostly because of strange obsessions. One fixates on imaginary health dangers like leptospirosis, then will jump into maniacal streaks. Another has a passive-aggressive problem. The worst of the lot fills his room with Nazi posters and icons and spouts fascist propaganda. It’s a very interesting choice on Gipi’s part to include such a character, especially given Italy’s history. It might strike some people as too offensive, but what makes the book truly impressive is that even this worthless, idiotic, piece of trash, Nazi-worshipping youth is crafted with such depth and feeling that you understand him, flaws and all. Gipi uses both little scenes with that character and the impressions of others to build the effect. In another scene with Giuliano and his girlfriend, she asks why he hangs out with the Nazi drummer. He says, “He’s just fascinated by the asthetic. He doesn’t know a thing about Nazism. He likes the uniforms, the leather trenchcoats, the insignia. In short, he’s an idiot.” That simple line explains all of them, their unrealistic goals and foolish mistakes in pursuing them, their failing efforts to not become their fathers.

Surprising for a book ostensibly about music, Garage Band contains very little of it. There are a few scenes of the band in mid practice, but Gipi almost always mutes the scene, giving the reader no idea of the words or structure of the song. Instead, he uses his art to establish the mood. Luckily, he’s skilled enough that it comes across perfectly. Gipi here uses often jagged, sparse inking that looks almost like doodles until you stare at it long enough and the complex structuring and delicate details emerge. His characters convey teenage ennui, always slumping or nervously scratching at an arm. And when they play, they overcompensate by leaning wildly and tossing their heads angrily. In some places, Gipi uses what could almost be called ghosting, leaving another inked head or arm almost behind the coloring. It implies motion, but also hints at the idea that these teens move outside themselves as they perform.

Similar to the inking, the watercolor coloring appears sloppy at first, bleeding over lines and ending in rough edges. And again, only under much closer view do all of the intricacies become visible, even with the smallest bit of color bleeding used to imply a character’s mood.

While so many books that fall outside of the superhero/adventure genre overcompensate by reveling in the tedious, Garage Band (and most of the upcoming foreign books) manages to overcome that, despite its simple premise. It does so by focusing on the characters, pulling them along a strange and surprising trail, watching them grow and change and fail and learn. It reminds me of Alex Robinson’s Box Office Poison, more than any other book. But really, it’s a thing entirely to itself, as scrappy and determined as a garage band.